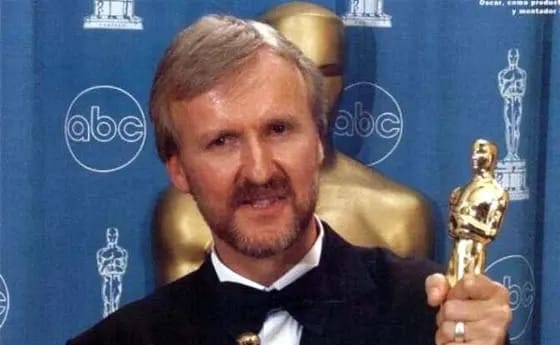

James Cameron

He's responsible for the sci-fi nonsense that is Avatar and its endless stream of sequels. But he does have one project nobody ever talks about...

The most successful director by career box-office earnings is, apparently, Stephen Spielberg. That shouldn’t be surprising. He’s had a very long, highly laudable career with 36 films under his belt. I think I’ve seen thirty of them. In third place on that list are the Russo brothers, of Infinity Wars fame, with eight directorial credits. Michael Bay is fourth, with fifteen. Peter Jackson is fifth, with thirteen. In second place is the subject of this piece, James Cameron, whose $8.8 billion in takings come off the back of nine directorial credits.

Cameron got his break in the industry courtesy of Roger Corman, who employed him in a number of special effects roles. After the original director left Piranha II: The Spawning, Cameron took the reins and finished the movie. His next project launched him into the stratosphere after producer Gale Anne Hurd took a risk on buying the script and letting Cameron direct. The result of that decision was The Terminator and the rest is history. Full disclosure, I am a huge fan of both of Cameron’s Terminator movies – Terminator 2 is still an incredible movie – and Aliens and The Abyss.

He has earned himself a reputation of being extremely challenging to work for. He drove out assistant directors during the production of Aliens, which also descended into open warfare between director and his British crew. In The Abyss, there is one long, brutal sequence where Ed Harris has to resuscitate his drowned wife, played by Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio. It’s harrowing to watch and Mastrantonio’s reaction to getting repeatedly slapped in the face and beaten on her naked chest by Harris under Cameron’s perfectionist promptings probably led to her eventual disavowal of the film, along with Harris'.

But I’m not talking about Cameron’s output as director, nor as producer. This is about one of his two credits as writer but not director. I don’t care about Alita: Battle Angel. I care about the 1995 sci-fi noir movie Strange Days, directed by Cameron’s former wife, Kathryn Bigelow.

Strange Days is not a famous movie. Made for $42 million, it only took $17 million at the box office. It received lukewarm reviews at the time and, since the start of the 21st Century, has been hard to find on DVD, video or streaming. I saw it back in 1995 at a press screening in Manchester. I remember being mostly unimpressed by it, but I’m not clear now as to why.

The film is set in the exotic then-future of pre-New Year’s Eve 1999, in a chaotic Los Angeles riven by racial strife and police brutality. Ralph Fiennes plays Lenny Nero, a sleazy former cop turned peddler of memories. The central conceit of the story involves memories, downloaded directly from the brain onto disk via a device called a SQUID. Lenny trades in these recordings. The film meanders around for fifty minutes of its 145-minute runtime, introducing Lenny and his relationships with his ex-girlfriend Faith (Juliette Lewis), PI and ex-cop Max (Tom Sizemore), limo driver Mace (Angela Bassett) and a few other misfits, Iris (one of Faith’s old friends), Philo (Faith’s boyfriend and manager of Jeriko One) and clip expert Tick. Lenny trades in clips, he mopes around after Faith, he loses his car to the impound yard, he pisses off Mace, who – for reasons never explored – tolerates his bullshit. It’s slow going.

Early on, in a sequence devoid of any apparent context, Iris is pursued by two renegade cops played by character actor favourites Vincent D’Onofrio and William Fichtner. Later, she goes to see Lenny who rebuffs her pleas for help. She drops a recording of a memory into his car.

Meanwhile, LA is burning. Rapper Jeriko One, a mash-up of Chuck D and Malcolm X, is murdered, further heating up the febrile atmosphere in the city in the very last days of the 20th Century.

And finally, with everything set up, we can actually get into the meat of the story. Thank God.

Lenny gets handed an envelope with a recording in it. When he watches it, it depicts the genuinely viscerally shocking and protracted rape and murder of Iris by a person unknown who uses a SQUID to force Iris to experience the emotions of her rapist during the rape. Yuck. Lenny and Mace investigate Iris’s movements and Tick tells them that Iris was looking for Lenny. They speculate that Iris may have left something for Lenny in his car and they break into the impound yard where it’s being kept. They retrieve the recording and are attacked and left for dead by the renegade cops.

Lenny boots up Iris’ recording. Iris was with Jeriko One when he was murdered by the same bad cops who have been hunting Iris, and now Lenny, for insulting the spotless record of the LAPD. This is obviously really bad shit and when Lenny and Mace return to talk to Tick, he’s been brain-fried by the people hunting Iris, who are also now looking for Faith.

Big decision for our heroes – will they trade the murder clip to Philo in exchange for Faith’s safety, or hand it to the Police in the search for justice and risk large-scale riots? Even for an oily prick like Lenny, there’s no decision here. Lenny eventually tells Mace to give the clip to the LAPD commissioner while he goes to find Faith.

In Philo’s apartment, Lenny finds Philo with his brain similarly fried as Tick’s. He watches the clip, which purports to show someone attacking and raping Faith, until the sex turns out to be rough but consensual between Faith and Max. Max explains that Philo couldn’t afford the loss of reputation from having his artists surveilled and so decided to have Max kill Iris, scramble Tick’s and Philo’s brains, and pin it all on Lenny.

Cue final struggle between Max and Lenny. Max plummets to his death before Mace deals with the bad cops, plus a little spontaneous police brutality, before the Commissioner arrives to arrest the bad cops. The new millennium arrives. The end.

There’s a lot to enjoy in this film. On a technical level, the clips are marvels of cinematography. In 2024, mounting a 4k GoPro to someone’s head and having them film a heist or sex from a first-person perspective is trivial. In 1995, Bigelow’s crew achieved this with 35mm film. The film opens with a first-person view of a robbery gone wrong and remains one of the strongest and most immersive cold openings to any film I’ve seen.

The performances are also good. Fiennes’ portrayal of Lenny as a cowardly, amoral weasel is convincing, even if he could stand to have played it tougher. Bigelow considered casting Andy Garcia as Lenny, which would have worked if steely Italian charm was what the story needed. Fiennes’ craven oiliness works perfectly. Bassett is fearsome and fiery as Mace and the ideal foil to Lenny. D’Onofrio plays his bad cop with brutish elan and Fichtner is all skeevy twitchiness. Lewis plays her patented tough-vulnerable starlet effectively. Sadly, Sizemore’s Max wanders through the story in a dissociated haze.

The story itself is where the film sails into troubled waters. Cameron and Bigelow are on record as seeing the project initially as a love story. While it’s fine to have Lenny pine for Faith like a lovelorn teenager, the unrequited love we are expected to believe Mace feels for Lenny is entirely unearned. Maybe the root of this lies in how the screenplay was created. Cameron took years to convert the base concept into a ninety-page treatment, which he passed to frequent Scorsese collaborator Jay Cocks. Cocks turned it into a screenplay and returned it to Cameron for a script ‘polish’ (love you, Big Jim Cameron, but dialogue maven you are not). I think Cocks would be your go-to guy if you wanted a contemplative drama, not a noir thriller. He doesn’t do a bad job, to be fair. But there is something missing.

I think I got this film wrong when I saw it in 1995. The misjudgement was entirely on my end – as an eighteen-year-old science undergraduate, I was unaware of much of the context and thematic content that Bigelow and Cameron were drawing from when they developed the film back in the 80s and early 90s.

One of the biggest themes relates to voyeurism. The SQUID and its clips are an inherently voyeuristic technology, one which the audiences of 1995 may have found hard to relate to. Nonetheless, the market for clips appears to be entirely male and their subjects of predominantly male, and prurient, interest – crime, violence, carnal knowledge of women. This would be more impactful today, when everyone has ready access to a camera on their phone. Pornography, too, is aimed at a majority male audience. Porn where men assault their partners is worryingly popular. In these matters, Strange Days is prophetic. I’m also going to praise Bigelow, Lewis and Iris’ actress for not depicting nudity or sexual violence in a coy or skittish way. It is confronted and displayed openly, with the intent to challenge and shock, and succeeds.

The other major theme pertains to police brutality. Cameron and Bigelow freely admit to the 1992 Rodney King riots playing a major influence on their conception of the story. Again, as a callow white British youth, the justifiably furious response of LA’s citizens to the acquittal of the police who beat King was something I was aware of, but not something I thought about. And again, the film is prophetic. Cases of police brutality were no doubt commonplace in the 1990s but rarely caught on camera. The murder of George Floyd, among others, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement will, hopefully, result in less violence from the police and more equitable outcomes within the justice system for minorities. As it stands, rising public anger at the continued mistreatment of African-Americans by the police brought people out onto the streets to protest over the deaths of ordinary citizens. Strange Days outright states that the murder of Jeriko One would result in war on the streets. Imagine if a popular, political rapper were to be gunned down by cops in this day and age and it were caught on camera. Open warfare sounds about right.

If Strange Days were to find a contemporary audience, or if it had been released in 2019, its cultural relevance and immediate impact would be far greater, except for a final issue.

There is a good reason why this film takes so long to get going. There is a murkiness to the story unrelated to its noir trappings. I could argue that a story about a disgraced cop hunting for a man who records himself committing rapes and murders would be story worth telling, as it explores notions of what is and isn’t acceptable within porn and voyeurism and the male gaze. But Strange Days doesn’t commit to this idea. Nor does it commit to the other theme, the potential story of two corrupt, murderous cops hunting down a witness to their murdering of an outspoken rapper. Instead, the story falls between two stools and spends an age setting all the elements up. Iris, who should be a key character in the story, gets two scenes before her ugly demise. Jeriko One gets no scenes at all until Lenny finds the clip of his death. Mace, who could have been a prime mover in the Jeriko One storyline, has no real purpose as a character except as an unrealistically competent counterweight to Lenny. In trying to tie all of the strands together, by trying to do too much through mashing both themes together, the film ends up essentially committing to nothing and this makes the remarkably pat and remarkably disconnected pair of endings unsatisfying.

A film with pretences at political and social commentary has to say something. Empty spectacle, as Strange Days ultimately becomes, inevitably will be forgotten. It's a curio, but an interesting one.