Tomorrowland

Disney do it again! Millions spent! Big names recruited! Wonderful production design! And the viewing public said "meh".

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: Walt Disney Motion Pictures hire a director from Pixar to write and direct a science fiction epic for a pre-summer release but it fails horribly at the box office and left almost no-one satisfied.

No, I’m not talking about John Carter. Andrew Stanton isn’t the only Pixar alumnus to burn hundreds of millions of Disney’s dollars in a well-meaning but flawed attempt to bring a sense of wonder to the box office. Brad Bird, he of Iron Giant, The Incredibles and Ratatouille fame, also suffered box office damnation for the House of Mouse, and for an entirely different set of reasons. His noble-but doomed movie was Tomorrowland.

Long before Tomorrowland was a movie, it was part of Disneyland. The first Tomorrowland opened in 1955, back in the days when science fiction was still all bright primary colours and wasp-like spaceships and everything about the genre was hopeful futurism and the sunny uplands of utopia. The original Tomorrowland was meant to showcase a potential 1986, sponsored by such public-minded corporations as Kaiser Aluminum and American Motors and, uh, Monsanto (presumably before Monsanto became completely evil). As time passed, Tomorrowland remained a popular attraction and Disney periodically updated it, but much of the design still retains that glorious 1950s future aesthetic.

Enter screenwriter Damon Lindelof. Those of you with good memories see the words ‘screenwriter Damon Lindelof’ and immediately feel an involuntary shudder. He was a writer and showrunner on Lost (ugh), mutated Prometheus from a true Alien prequel into the tolerable chimaera we all know and think was OK, shat out the dud that was Cowboys & Aliens, and then completely failed to appreciate what World War Z was actually about. The bigwigs in Hollywood may have respect for Lindelof’s work, but I don’t. Lindelof had a hankering to turn the name and central concept of Tomorrowland into a movie, and to give the devil his due, a retro-futuristic sci-fi movie about the futures we didn’t get is a cool concept. So, he approached Disney and got to work on developing his idea into an actual story.

When Brad Bird got attached, he added his voice to the writing. Bird was interested in how sci-fi and futurism lost its optimism, and lo! they had a theme and from the theme a story. Bird certainly seemed like a good fit for the project, especially after critical or commercial success in the past. The Iron Giant failed at the box office but remains a critical darling. The Incredibles is the best superhero film ever made. Ratatouille is wonderful fun. His Mission Impossible movie, Ghost Protocol, is a solid entry in the series too. And prior to all of that, he’d had a good career as an animator and a writer-for-hire, and that includes eight seasons of making The Simpsons.

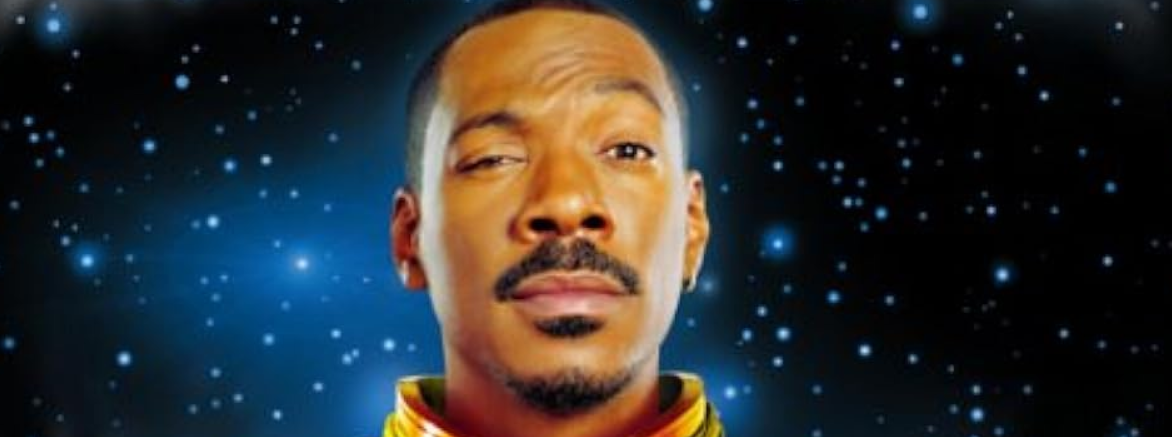

Actors were attached: the big name being George Clooney, a smaller name being Hugh Laurie, and production progressed. Disney leaked bits and pieces about the setting, changed the name from 1952 to Tomorrowland and went and shot the movie.

Tomorrowland begins with a framing device that make me want to claw my own brain out. Frank Walker (Clooney) is giving a talk about something, but thanks to an annoying off-screen interruption (Britt Robertson, playing Casey), he doesn’t get very far. Apparently, as a boy, Walker attended the New York World’s Fair with his jetpack, but grumpy scientist Nix (Laurie) isn’t interested because it doesn’t work. However, a young girl, Athena (Raffey Cassidy) gives Frank a magic pin-badge and tells him to follow her. They enter a magic portal under the It’s a Small World ride and are whisked into a futuristic city of Tomorrowland.

Back in the present day, the hyper-optimistic Casey is busy annoying literally everyone in the movie. She’s angry at the negativity of her teachers, the learned uselessness of her NASA engineer father, and spends her evenings sabotaging the demolition of a NASA launch site at Cape Canaveral. Eventually, she is arrested for her crimes but is bailed out, whereupon she discovers a pin-badge in her possession which transports her into Tomorrowland. She has a jolly fun adventure there until the battery runs out.

So now Casey is totally sold on Tomorrowland and wants to get back. She tries to find out more about the pin-badge and goes to Houston for info. The owners of a memorabilia shop want to know where she got it and attack her, whereupon Athena rescues her in a fun little nostalgia-fest action sequence. The shop owners, it turns out, are robots, and so is Athena. Athena reveals she is on a mission to recruit people to join Tomorrowland and takes Casey to see the now adult Frank.

Frank isn’t receiving visitors and has become an old curmudgeon. He eventually lets Casey into his house and reveals the world is doomed, but somehow Casey has the power to prevent it. Then robots attack, Frank fights back and he and Casey escape. They meet up with Athena and Frank is still mad that Athena is not a human (kid Frank fell in love with her) and the three of them teleport themselves to the top of the Eiffel Tower, which turns out to be a secret steampunk rocket launch site. They commandeer the rocket from beneath the Tower and launch themselves across a dimensional barrier into Tomorrowland.

But Tomorrowland is no longer the happy land of wonder it used to be. Nix has let it go to shit, and refuses to do anything to help prevent the destruction of the other Earth, as predicted by Frank’s invention, the Tachyon Machine. Casey’s optimism is still affecting the machine. She realises it is the Tachyon Machine which will destroy the Earth but Nix doesn’t care and decides to maroon our heroes on a desert island.

There is a brief action sequence in which Nix gets crushed by a falling piece of scenery, Athena gets damaged to the point where her self-destruct device is activated and she persuades Frank to throw her into the Tachyon Machine so she can explode and destroy it. With the world saved, Casey and Frank build more robots like Athena who will begin searching for more dreamers to rebuild Tomorrowland.

On one hand, it’s a tragedy that a film with so much heart, filled with so much hope, failed at the box office. On the other hand, it’s no surprise at all that a film which forgot the rudiments of story-telling should do so poorly. Tomorrowland is all heart and no head.

As usual, I want to begin with the positives. Tomorrowland is a gorgeous visual treat. Production design: chef’s kiss. Special effects: chef’s kiss. Action choreography: pretty good and often funny, thrilling or both. I loved that they made Athena an ass-kicker. It’s so incongruous and unexpected to have a little-girl robot be the biggest of bad-asses, and somehow the film makes it work. The creativity on display for the visual aspects of this film are glorious, and everyone should be proud of their contributions.

However, it keeps happening. It just keeps happening. I’m going to give it a name. Hollywood Blockbuster Character Syndrome, HBCS. Of course, I am neither a screenwriter, nor production executive, so I don’t know precisely what happens out there during pre-production. I do read, and I do write, and I think a lot about how I want my characters to be and behave. Deleteriously thin characters aren’t a thing in good fiction. You can’t get away with it in most genres. But, for some reason, in an industry where millions are thrown at screenwriters and month upon month spent rewriting screenplays, characters as insubstantial as shadows seem to be the rule.

This doesn’t make any sense. Way back in the mid-1990s, I wanted to be a screenwriter. Pulp Fiction and Leon comboed me into it. Bam-bam, that was awesome, I want to do that. And part of my studies of screenwriting was a website called wordplayer.com, created and maintained by Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio, the writing duo behind some big old hits like, er, Shrek and Pirates of the Caribbean. They know their shit, basically, and when their writing works, it’s fantastic. They created a checklist for their screenplays. When the writing hits all the boxes, the screenplay will probably work. Here it is, and we want to scroll down to Checklist C. Characters. Point 47. “What are the characters wants and needs? What is the lead character's dramatic need? Needs should be strong, definite – and clearly communicated to the audience.” Right at the bottom of the column, the writers discovered their checklist was being used by production companies to vet screenplays. None of this is new thinking.

Fast forward to Lindelof and Bird working on the screenplay for this movie. Yet again, highly-paid and well-regarded creatives forgot to write rounded characters into their movie. I cannot begin to tell you who Casey is as a person, other than ‘optimistic’. She has a want: to get into Tomorrowland, but this want is imposed on her by the story. It is not an essential aspect of her character. There is no need to play the want against. There is no inner struggle. There is no hidden wound or secret fear. She is obnoxiously loud and ridiculously optimistic and that’s yer lot. She’s supposed to be special in some way, but she never demonstrates much in the way of abilities. Maybe those scenes got left on the cutting room floor.

If Casey is the protagonist, she’s a bad protagonist. But I think she isn’t. The protagonist makes the decisions which drive the story. Casey demonstrates very little agency from the mid-point on. What about Frank? Well…he’s a much better fit. He has a need – save the world – but he’s perfectly happy to lurk in his house and let the world end. He’s hyper-competent and grumpy. No drive, though. No motivation. Which leaves…Athena. Curiously, could the protagonist of this film be a robot in the form of a twelve-year-old girl? She lets Frank into Tomorrowland. She recruits Casey and saves her in Houston. She takes Casey to meet Frank. She dies to save Frank and then explodes to save the world. But, here we go again, where’s the emotion? The narrative drive? Athena is simply fulfilling her programming. She facilitates the plot, much like Gandalf in Lord of the Rings, but she isn’t the protagonist.

So we have a story without a protagonist and with characters which are almost too thin to survive examination. Tomorrowland is a story which is dominated by the spinning wheels of a plot. Things happen because the plot says so, not because the characters make it happen. It’s meant to be a story about the transformative power of hope and optimism, but it fails to give us a character to actually care about. If Casey is the protagonist, she is the blandest one possible. If Frank is the protagonist, he can’t disappear from the movie for an hour, like he actually does.

HBCS is not the only screenplay problem. It takes ninety minutes to get our gang of three into Tomorrowland to find out what the big problem even is, and then we’re immediately into act three and the big climactic action sequence. We never get to see why Tomorrowland fell apart and has become a corrupted shell of itself. We don’t even get the cliched ‘all-is-lost’ moment modern story theory is absolutely obsessed with. Yes, there are stakes. Yes, the action is well-choreographed and exciting. It feels incomplete. I felt like huge chunks of character development and story were missing. Tomorrowland functions like a collection of action sequences all muddled up together with no notice paid to logic or motive.

I didn’t care about the characters and in the end, I didn’t engage with the story. Tomorrowland simply doesn’t work as a story – it feels like a bunch of cool concepts bolted together with the hope they come out as a coherent whole. Once again, we’re back in empty spectacle country. Yes, the message is lovely, and sorely needed. Whatever happened to the hope that guided sci-fi in the Fifties and Sixties? We need it back. Tomorrowland was the right vehicle to deliver that message, until they forgot how stories work, again. What a great shame. I wanted to enjoy it. I truly wanted to. Watchable, but hollow.